Bridge addicts adapt to Covid

In order to survive Covid much changed, not just life, but also the things that enrich it. When the restrictions of lockdown made face-to-face bridge impossible, for example, addicts like me were forced to play online.

Not only did most of us make the leap from bridge table to computer screen easily, but we also found on-line bridge one of the more enjoyable aspects of lockdown. If, like me, you find the social aspects of club bridge more important than the game itself, then on-line bridge is a terrific substitute, but not the same.

It changed both the game and the way it was played and threw up some surprising advantages. It was, for example, impossible to revoke, lead or bid out of turn, surely something to be welcomed. But some people hated playing online, and not just the minority who believe computers are monsters in disguise and best ignored.

For the average club player bridge costs next to nothing; it’s so cheap that it undervalues the game. Playing online wasn’t expensive either. Sadly bridge has been in decline for a generation or more. Playing cards is no longer a major component of our social lives, millennials sneer at the game as if it were something the cat brought in and serious enthusiasts like me have got older.

Bridge didn’t just survive Covid, for those who played online it thrived. But I suspect that sadly there aren’t as many playing regularly now than there were before the pandemic. When face-to-face duplicate returned in the autumn some clubs struggled to fill more than four tables. Some former regulars, justifiably, remained terrified of Covid. Others found that they hadn’t really missed the game, at least not by enough to encourage them to venture forth on a foggy November evening.

Learning the basics

I learned the basics of bridge while sitting next to my father when he played with his two brothers and my grandfather. Hovering above the round table and thick beize cloth was a swirling cloud of cigarette smoke; my grandfather and his middle son were sixty-plus-a-day men.

Please note that I didn’t learn to play the game, just grasp the basics. My grandfather didn’t have much card sense, his three sons did, but their bidding was so appalling and the hand evaluation so misguided that they were forever finagling their way out of disastrous contracts.

Too many people don’t see bridge as just a game of cards. They growl at every failed finesse, see doomed three no-trump contracts as a matter of life and death and blame every losing score on the incompetence of their long-suffering partners.

There have been periods in my life when I haven’t played at all and the fact that I still do is down to the French. Although the two countries have always had their difficulties, the French get so many of life’s basics right.

I was in Les Carroz, a ski resort in the Alps between Geneva and Chamonix and living five minutes from the bridge club which meets twice a week in the winter and plays between 5-7 pm. Sometimes they might struggle to make up a table; at others there can be twenty players or more. They meet more frequently in the summer.

It was there I found Denis, or rather he found me, and we played as partners twice a week for the next two months. The French play five-card majors and a 15-17 point no trump together with Stayman, transfers in the majors and Roman Blackwood. Similar, you might think to Standard American, but compare it to that at your peril. Standard French it is.

Located in the first floor of a modern school, the club is well equipped with plenty of tables and all the accessories necessary for a duplicate session. There is no table money; everything is free. Everyone is warmly welcomed with handshakes between the men and, once they know you won’t bite, warm hugs from the ladies.

The use of bidding boxes avoids the need for fluent French, but it’s as well to be able to count and know the suits: pique, coeur, carreau and trèfle for spades, hearts, diamonds and clubs; no trumps are sans atout. The court cards are l’as, le roi, la dame and le valet for ace, king, queen and jack.

For those whose language is up to the mark, there are some lively post mortems which can help the less experienced, enlighten the few who think they’ve seen it all before and point out mistakes, possible alternatives and safety plays.

In England it was the aggression of the obnoxious minority that made me give up the game; in France it was the genuine warmth and enthusiasm of the company that brought me back.

I’ve played in the US, too. Having had the corners of my game knocked out of me at the Acol Bridge Club in West Hampstead, I was committed to the weak no-trump and all that follows. But adapting to Standard American wasn’t difficult and I mostly used a strong no-trump and five-card majors when playing on line.

My own game changed for reasons other than Covid and this explains the image above, the Helmingham Deer Park in Suffolk. After living for over thirty years in Cornwall, I moved to East Anglia and have so far played in three different clubs: Beccles, Lowestoft and Bungay. Their personalities are all subtly different. In my experience so far Beccles has the highest standard, Lowestoft for me is the longest drive (eighteen miles) and Bungay the most comfortable as during the winter it’s held in the local golf club and the beer is good.

*****

Author Ian Fleming was a member of the Portman Club, where the famous card scene from the 1955 novel Moonraker takes place, but he borrowed the deal from Ely Culbertson, the American writer who helped popularise bridge in the 1930s and 1940s.

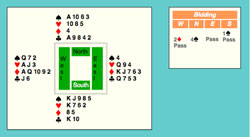

Bond, siting south and partnering his boss M, is playing seven clubs doubled and was out to beat the villain Hugo Drax who was sitting east with a rock-crushing hand including three ace-kings and the king-jack of clubs.

The full deal, known as the Duke of Cumberland hand, was prepared in advance by Bond who switched the cards behind a handkerchief he pretended to use to wipe perspiration from his face.

It is easy to see that Bond’s contract is undefeatable against any defence. Interestingly, the contract is unlikely to have been bid at anywhere other than the Portland, which had banned bidding conventions other than strong two openings and take-out doubles.

Sometimes the best thing about bridge is the opposing pair’s arguments, particularly if you’ve not had the cards.

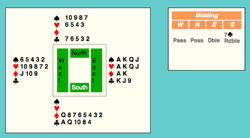

But no row beats this one. It was dealt by a John Bennett in Kansas City in 1931. He was sitting south and partnering his wife Myrtle in a social game with another couple, the Hoffmans.

John opened one spade. West, Mr Hoffman, over-called with two diamonds. Mrs Bennett, North, raised to four spades which became the contract.

Hoffman led the ♦A, but switched to the ♣J when he saw dummy’s singleton. John won the king and drew trumps. Sadly, he went one down.

Myrtle was incandescent, raced to her mother’s bedroom, grabbed a pistol, pointed it at her husband, shot and killed him.

I have no details of what happened next. No matter. She was tried for murder and acquitted. Perhaps there were a few bridge players on the jury.

All these years later the question remains: did Bennett deserve to die of lead poisoning?

He’s a little short on high card points for his opening bid, but she wasn’t strong to raise to game. If Myrtle had known and used the Losing Trick Count she would have counted her eight losers, correctly assumed that her partner had seven losers and deducted the total (7 + 8) from 18 and bid three which he would have passed.

If you look at the cards again you’ll see that John might have saved his life by playing it better. After winning the K♣, he should ruff a diamond with a small trump, lead a trump from dummy and go up with his king.

Follow that with the 10♣. Hoffman would cover with his jack and declarer would win with the ace in dummy.

John should then lead the eight or nine of clubs and ruff it letting Hoffman over ruff if he wanted to.

If Hoffman wins and leads a diamond or heart Bennett’s contract is saved. A trump lead makes it more difficult, but at least declarer would have done his best of it and given himself a chance to land the contract and stay alive.

After years of being hooked

on Acol and the preemptive advantage

of opening a weak no trump (12-14),

an increasing number of top players

are switching to a strong no trump and

five-card majors because it’s more

precise, making it easier to find

the best part score.

Many of them are using this book.

Recent Comments